Urinals and AI in Art

Last updated: June 24, 2025

Background

Machines are embedded in art so deeply that we don’t even really notice them. Most writers don’t think it’s a perversion of their work to type it on a computer. Even the most conservative likely doesn’t deactivate the spell check built into Google Docs or Microsoft Word. But that same writer probably rebukes ChatGPT and regards AI-produced writing as second class, in hypotheticals and when they can spot it. Fundamentally, a lot of artists don’t regard AI-generated art as art. Some instances of engineering in art are acceptable, though; they might defend the honor of an artist who uses a tool like Procreate to create animations and drawings. They appreciate the daring of a readymade sculpture.

As the conversation around AI art becomes louder and more frantic, especially after the launches of Veo 3 by Google and 4o Image Generation by OpenAI, I thought it would be interesting to look at Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a piece that altered the course of modern art history and forced an expansion of the criteria that define art. Right now, the definition of art is being challenged in some fundamental way - it seems to mean something new and different for algorithms to make art products that we consume. Our social media feeds, ads, and even galleries are being populated with them rapidly. But the academic definition of art has changed many times. Engineered products aren’t new to art by any stretch of the imagination. So what’s actually changing now? Is this a bigger and more fundamental shift than those that have come before? How does the intrusion of AI into art making fit into the historical progression of modern art? How does it compare to the shockwaves felt post-Fountain?

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp (1917)

Fountain is a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt”, submitted for the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists with Duchamp’s assertion that it is an everyday object “raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist’s act of choice”. Fountain wasn’t displayed in the show area of the exhibit and the original has been lost. It ended up being displayed in Alfred Stieglitz’s studio and published in The Blind Man.

This work now lives at the heart of the 20th century discussion around what constitutes art, “which more than any other experiment has challenged the boundaries and even the foundations of art as a concept” (Goldsmith). Although Fountain was initially met with chuckles and repulsion, it ultimately was accepted into museums and displayed on a pedestal, as Duchamp had intended. It locked itself into the course of modern art history and prompted a wave of celebration of everyday objects, sometimes as commentary on consumerism and advertising. Andy Warhol in particular was highly influenced by Duchamp's work: "Therefore, everything seen - every object, that is, plus the process of looking at it - is a Duchamp. Turn it over and it is" (1963).

Campbell Soup Cans by Andy Warhol (1962)

Relationship to AI

The act of creating an art product with generative AI is reminiscent of Duchamp’s process. The user inputs a prompt - their will - to a chatbot, which returns an image. Is the image art, considering that Fountain is? There doesn’t seem to be a huge difference between writing a prompt and receiving a visual representation of it as compared to having a thought and applying it into a pre-engineered urinal and saying that it was your unique human brain that justifies its presentation in a museum.

I’m sure there are artists and art critics who would disagree with that comparison. The consensus seems to be that Duchamp did something original by realizing that there was something to be said about what we accept as art. A person who uses an image generator isn’t doing something for the first time. They’re using it as a tool to circumvent the great struggle associated with developing and applying one’s technical art skills to a paper or block of clay. They’re using it to avoid figuring out every detail of the output, another key element of art of the past. There are a lot of romantic notions about how a painter knows everything that goes onto their canvas and that everything has a purpose. Chekhov’s gun lalala. But AI might put something in your output that you didn’t explicitly ask for or intend. The AI-generated gun won’t necessarily be fired, which defies our expectations as viewers.

Richard Kuhns, in Art and Machine (1967), writes that Duchamp’s “discovery” of the readymade introduced two big ideas into art - the engineered itself as an art form and chance as artistic choice. AI in art certainly allows for an appreciation of both the engineered and chance. When we see a startlingly real-looking live comedy show, we don’t praise the prompter of the video, we praise Gemini’s engineering triumph. Complete precision is impossible - the user doesn’t prompt every pixel. If you ask ChatGPT to paint you a blue sky without specifying the shade, you leave it up to chance. You still imagine a blue sky, but you don’t determine exactly what it ends up looking like.

Is AI just a tool?

As of now, sort of. NVIDIA’s AI Art Gallery site says that artists are using “generative AI as a tool, a collaborator, or a muse to yield creative output that could not have been dreamed of by either entity alone”. In the way that there are painters and sculptors, a new type of artist is emerging - one whose medium is these models. But because AI labs are aiming to create agents not reliant on human intervention, any description of AI as a mere “tool” seems, if not outright deceptive, temporary.

A big part of what people found disturbing about Fountain was the complete lack of physical intervention by the artist. Duchamp didn’t do much except have the idea, sign the urinal, and show it to people. AI also enables the creation of art with barely any effort on the user’s part. It can do an artist’s whole job nearly end to end. The necessity of writing prompts and making edits are really the only steps that make AI permissibly describable as a “tool”. But as these agents get better, they’ll be able to eliminate, or at least corrupt, the act of thinking as a step in creation. If you don't know exactly what you want to make, you can prompt an LLM for a prompt. AI, if it can’t already, will be able to rob the artist not just of the technical effort of creation but the thinking that they treasure so deeply. It was human thought that made Fountain into a “sculpture” and induced one of the most important inflection points in modern art history. A traditional artist might wonder: when both the effort of creation and the artistic intentionality aren't human, what’s left?

Consumers of art

I think it's helpful for this discussion to bucket off the two primary ways that people relate to art: as consumers and producers. Most people have traditionally been consumers: connoisseurs, critics, enjoyers. We listen to music even if we don’t make it. The consumption of art and how a viewer relates to the artist, even without the introduction of AI, is complicated - there’s a lot of discourse about whether you can separate the art from the artist. Kanye West comes to mind. Some people have avoided listening to Kanye because of his anti-Semitism, but a lot of people still really enjoy his music and play it - he had more than 60 million listeners this last month on Spotify. He’s had a lot of influence in the music industry over a long and storied career and he hasn’t just been eliminated from fans’ playlists. But even beyond controversy, an artist being helped by other people isn't usually a dealbreaker for the consumer: many mainstream pop stars sing songs by ghostwriters and even Michelangelo had assistants helping him paint the Sistine Chapel. I’m writing now at a point where AI art hasn’t totally saturated the places we consume art. But it’s getting there. And consumers, though some are very picky, tend to be willing to overlook a lot authorship-wise if they like what they're seeing. People are falling in love with chatbots already! As their context windows widen, these models become increasingly capable of making us feel - which for the average painting-looker or music-listener is most of of what they’re seeking in their day to day interactions with art. If you’re someone who likes art but doesn’t care enormously about where it comes from, AI might be a nice enhancement to your consumption experience.

Tim Schneider takes a more anti-AI purist perspective in his Substack post critiquing Sam Altman’s “The Gentle Singularity”, arguing that ideas and production volume run counter to what makes art great. He writes that we don’t need more art - that we were already drowning in it before generative AI made its production so effortless and thoughtless. He quotes Neal Stephenson on a 2024 podcast.

“The real purpose of art and the reason we like art is because it exposes us to a very dense package of micro decisions that have been made by the artist. As such, we’re engaged in a communion with that artist. What makes it interesting is that connection. It may be to a living writer, or it may be to a sculptor who died 2,500 years ago, but in either case, we’re making a human-to-human connection. If we know that we’re reading something or experiencing a work of art that was just generated by an algorithm, then that element of human connection isn’t there anymore.”

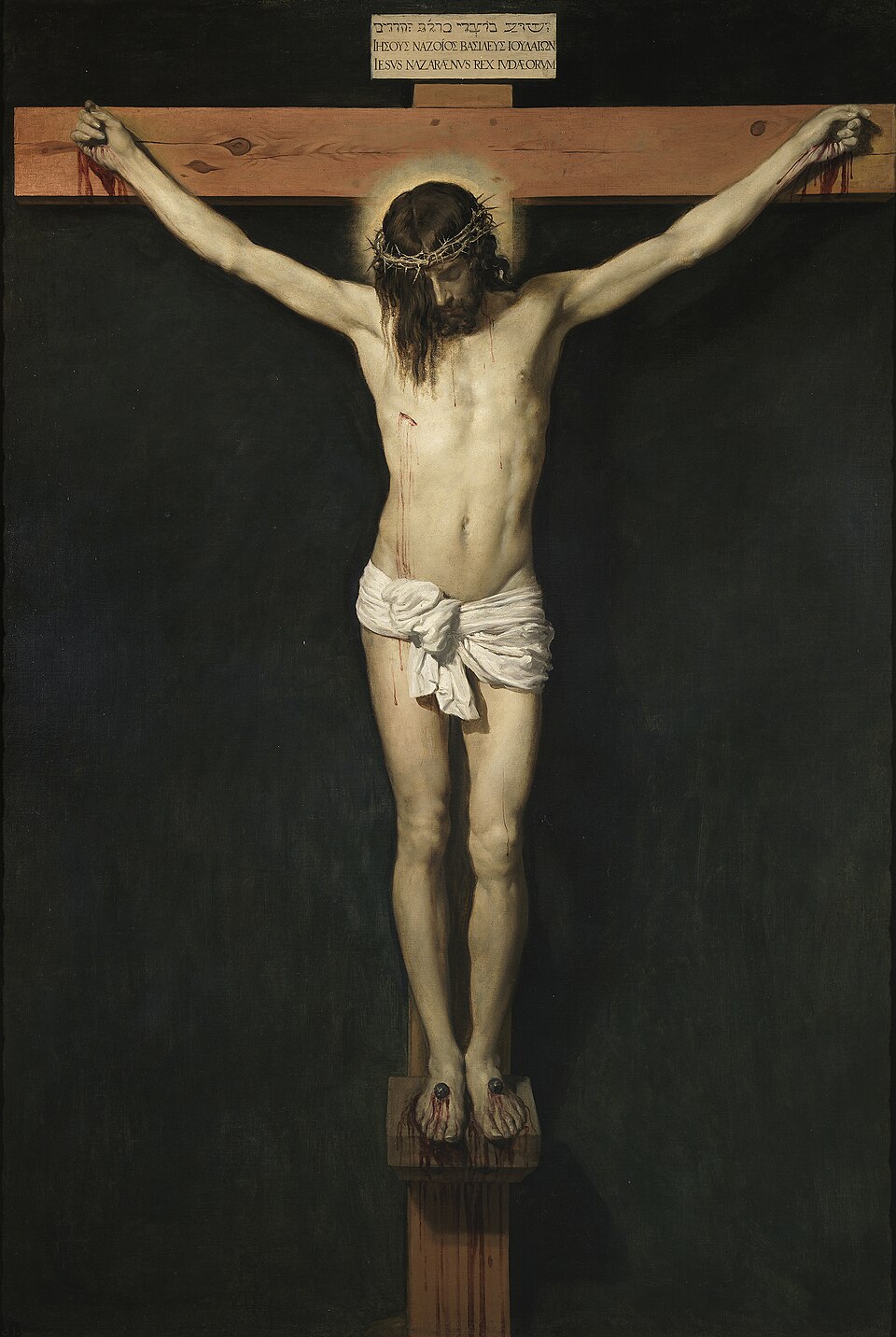

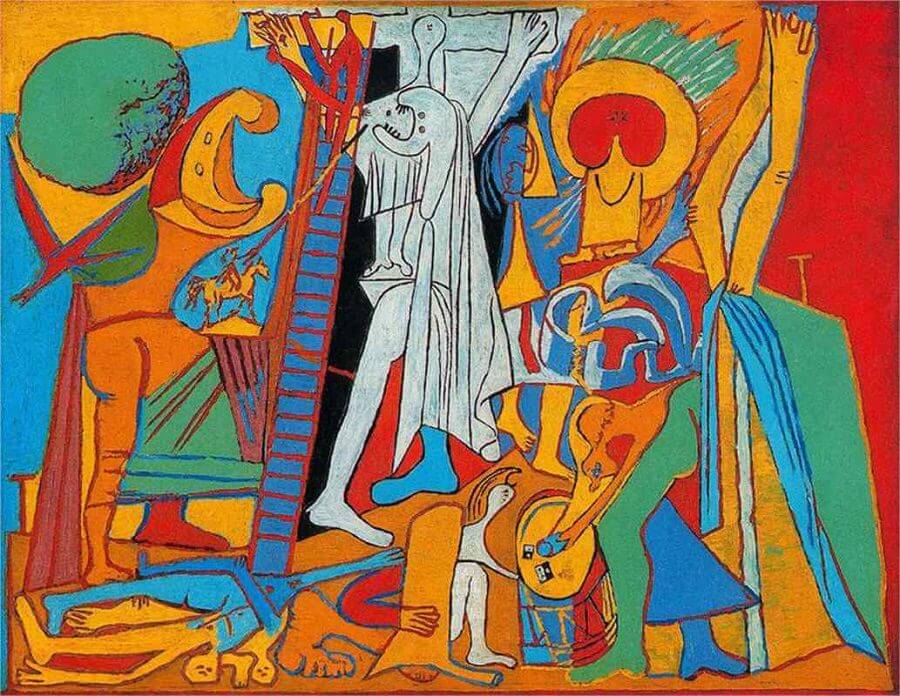

Schneider believes that tiny choices are what drive us to seek art. AI lets the artist make big choices rather than small ones, hollowing out the meat of the artwork that he argues the viewer is looking for. There are surely thousands of depictions of the crucifixion: the same scene painted or sculpted again and again by artists across centuries and cultures, differentiated only by minute artistics decisions of how to proportion the body on the cross, which characters to include, and the level of agony to portray on Jesus’ face. These choices make each painting vastly different from the next, even though the story is the same.

Christ Crucified by Diego Velázquez (1632)

Crucifixion by Pablo Picasso (1930)

So what actually matters to people when they consume art? Fountain proved that what we accept as art has changed over the last century in a fundamental way - nearly everything can be art with very little physical effort by the artist. And although some art lovers are strict about what they look at, anecdotal evidence points to an overwhelming laziness in people on almost everything, especially in their consumption.

Producers of art

Art can be done as a means to an end or as an end in itself. Art as a means to another end is typically sold to clients or submitted for grading in schools - the examples that immediately come to mind for me are graphic design, video creation, and written content. If your goal is to create a certain output by a certain time, it makes sense to use shortcuts to get there faster: AI is the most capable shortcut we’ve ever discovered. Artists who leverage AI to create art products can do their work more quickly and produce higher quantities of it. People who used to commission artists for their work can now skip that expense and make the art themselves.

We’ve historically worshipped the notion of artists doing art as its own end and always taking the long way. Van Gogh didn’t become famous until after he died - he sold one painting during his lifetime, but went on and on at that canvas until he lost his mind and produced some of the most recognizable pieces in the world.

Producers of art are being split into a few categories:

Traditional artists who reject AI

The traditionalists are in a tough spot. Of course, every industry is grappling with the ability of AI to do what they do. But it seems like a big part of what makes these artists so defensive of art is that they love the process of creation - a process that is historically slow and personal. You don't get a ton of professional artists who are in it for the money (a different end) or who want to speed through their work as quickly as possible. On the other hand, not every software engineer truly loves debugging - that’s why so many are now using AI to quit their big tech jobs and make startups. It’s more fun to ship products than to agonize over every line of code and the incorrect placement of a semicolon. Artists, arguably more than other professions, tend to find honor in struggle and process more than output - which places them at odds with technology oriented around production and efficiency.

Artists who are embracing AI to make new things

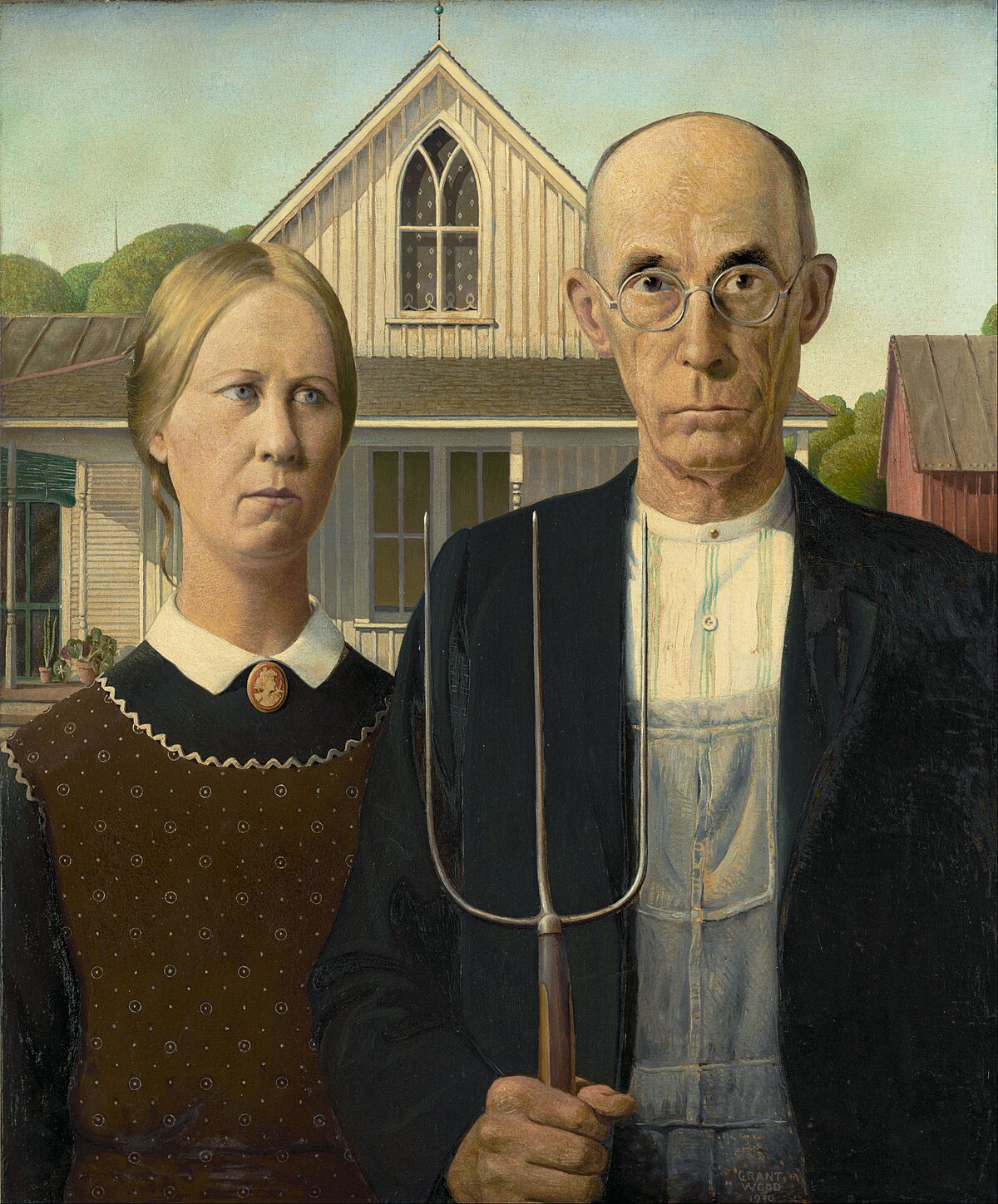

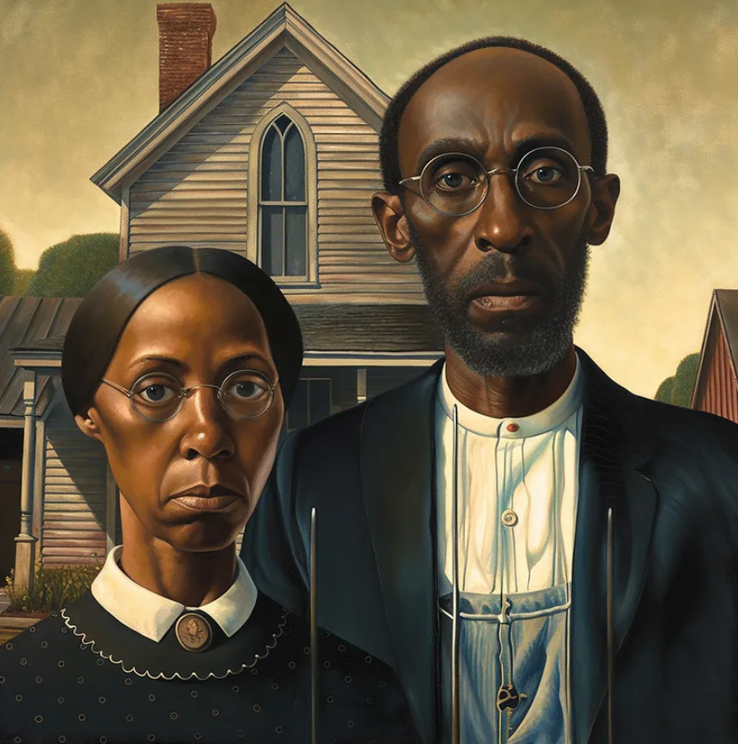

There's certainly a growing body of artists who are using AI to make interesting statements. There are a lot of cool applications of AI in reimagining famous art pieces, for example. Here are two iterations on Grant Wood’s iconic American Gothic: VIRTUAL AMERICAN GOTHIC by gala_mirissa and New American Gothic, created on Midjourney by Nettrice Gaskins and included in her Medium blog post. I can't include the full VIRTUAL AMERICAN GOTHIC experience but you can check it out for yourself here. Attaching below the original American Gothic and New American Gothic.

So in some ways, AI is a democratizing power in art production. People who have things to say can open their computer and state their thesis without having gone to art school or studied the classics for years. Considering how expensive art production can/used to be, this is pretty powerful.

Some artists say that AI is supercharging their creativity and helping them to think faster and more clearly. A Substack post titled "it's my party and i'll use ai if i want to" by Stepfanie Tyler is interesting and gives insight into this perspective.

People who use AI to make art products but don't consider themselves artists

AI is easy enough to use that it blurs the line between producer and consumer. As I mentioned earlier, it's becoming much simpler for people who used to commission artists for their work to use AI to make that art themselves - for advertising, social media content, written materials, and more. But even beyond commerical deals, a lot of AI users create art that is highly personal to their interests and tastes. Is this where "slop" comes in? Slop is worth further exploration.

Aside

I didn’t use AI for this essay because I wanted to sit with it and think about it. It took way longer than it would’ve if I had asked an LLM for ideas or to restructure my notes. It's not quite finished either - there's so much to say about all this. I like the struggle associated with writing and knowing that this all came from my head and other authors. There wouldn’t have really been a point in writing this if I had outsourced it to a chatbot. But this is also just for fun and I'm not trying to sell this to you or even perfectly answer my own questions. I didn't want to dirty up my thinking by putting it through a model, which I might've felt differently about if I was just trying to get the piece finished.

If AI is doing something for you, you’re not doing it. And that’s fine - we don’t need to do everything anymore. It makes sense to offload repetitive work and to use it to make stuff more quickly. But I try not to delude myself into believing that AI is just helping me “think better”. AI thinks really well and we can ask it to think about our problems and to give us ideas. But looking at the answers to a test and realizing they make sense doesn't mean you got the answers. AI gives us hyperspeed - my favorite writing comes slowly and in small steps.

In sum

I'd bet that AI-free art will never fully die; some people will always have the urge to create on their own. Artists didn't stop painting after the invention of the camera and didn't stop sculpting after the emergence of the readymade in 1917. But running contrary to the deep resistance to automation on the producer's side is apathy and flexibility on the part of the consumer. We like what we like and even if we don't like exactly where it came from, we can pinch our noses. The definition of art has widened before and can again.